Post by Gilberto on Mar 14, 2013 17:25:25 GMT -5

I like to think of the period following (and even prior to) the release of the first film as the frontier period of the Expanded Universe. With the least amount of source material to work with, creative teams behind the licensed properties had to reach deep to come up with Star Wars stories. This innovation brought a lot of fun and original ideas into the mix, but it also led them down a lot of wrong directions that left those stories too far from center to be considered canon when the formalized structure of the Expanded Universe was established many years later.

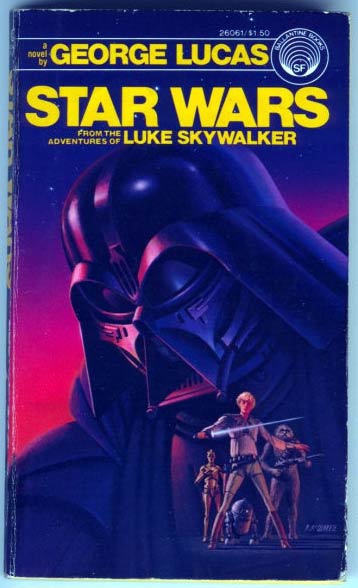

Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker was first published in December 1976. It has the distinction of being the first entry in the Star Wars universe that was distributed to the public, having been released half a year prior to the opening of the first film. It is also technically the very first published work to contribute to the Expanded Universe.

While the Star Wars novelization was produced as a promotional tie-in to the film, and was therefore not intended as an expansion on that world, there are some strong points I’d like to make as to why it deserves some minor consideration as an expanded work.

The book is credited to George Lucas but was ghost written by science fiction author Alan Dean Foster. The fact that it provides details and insights into the Star Wars lore is not enough to qualify it as an expanded work. Foster was working from earlier drafts of the script that had scenes and details not included in the finished film. This is not uncommon for novelizations of movies, since the novel’s release has to coincide with the release of the film and therefore the finished film is not available to the author while the novel is being written.

The novel, curiously subtitled From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker, offered fans some glimpses of the Star Wars Universe that were not revealed in the film, some of which never would be. The prologue sets up the story much the same way as the opening crawl of the movie but it references a historical chronicle called the Journal of the Whills as the source of the information. The Journal of the Whills was a hold-over from an earlier draft of the screenplay. The history it sites differs somewhat from what the canon will later offer. While the back story of Palpatine rising to power and declaring himself Emperor remains the same, the Emperor is portrayed as kind of a lame duck whose Empire is overcome by over-ambitious subordinates. The Imperial Governors are more responsible for the corruption of the Old Republic than he is, and they ultimately carry out the destruction of the Jedi Knights. The Emperor in this version of the story is isolated and allows his Empire to be picked apart by forces he can no longer control. The Imperials in the book have no real respect for him, and even Vader has a sardonic air when vowing to carry out the Emperor’s will. No suggestion is made in this or any work prior to The Empire Strikes Back that the Emperor is a master of the Force or that he has any influence in that regard at all.

The argument that the Imperial Governors had more or less assumed control of the Empire from Palapatine is supported indirectly in both the film and the novelization. Tarkin unilaterally makes decisions about how to use the Death Star and fight the rebellion, and nothing is said about contacting the Emperor for confirmation of these decisions. He blows up Alderaan and sentences Leia to death without so much as a phone call to see if either of these actions is consistent with the Emperor’s master plan.

There are other slight differences from the film canon. Leia’s message to Obi-Wan Kenobi says she represents the Alliance to Restore the Republic. They probably should have kept that name. It’s a more dignified name for a legitimate organization than the Rebel Alliance, as they become called in the films.

Like a lot of expansions/adaptations of the first film, the Star Wars novel included a more detailed look at Luke’s life on Tatooine. Biggs Darklighter meets him at Anchorhead to reveal his plans of joining the rebellion against the Empire. Luke’s Tosche Station crew includes the surly mechanic Fixer and his girlfriend Camie, as well as his friends Windy and Deak.[1]

Their involvement in the novel is consistent with similar scenes in the Marvel Comics adaptation of the film and the Star Wars Radio Serial. Both of those works follow this one, so the inclusion may mean they used the novel as source material. It may just be that all three works used the same source material and the Anchorhead scenes appeared in an earlier draft of the script.

It’s clear that Lucas wrote scenes that showed more of Luke’s life on Tatooine, at least enough to cover his conversation with Biggs Darklighter. That scene was actually shot, but was never reintegrated into any of the successive iterations of the film.

Darth Vader goes back and forth between being humanized and demonized in the book. One description of him says red eyes glow from inside his mask, suggesting that his natural eye color is a glowing red. In another scene he uses the Force to float a drinking cup into his hand. That doesn’t preclude his being inhuman, but it does sort of break his imposing presence when he starts drinking coffee through his breath mask.

The novel doesn’t identify the liquid in the cup as coffee, but Howard Chaykin illustrates it as though it were a steaming cup of coffee in the Marvel Comics adaptation. I assumed this to be simply artist’s license until reading the novel and finding that the scene is depicted there as well.

General Tagge is much more aggressive in the book, mostly because his character has been transposed with Admiral Motti, otherwise known as “the guy Vader choked in the Death Star conference room”. The result – being choked – is the same for Tagge in the book as it was for Motti in the movie, but his opposition to Vader helps establish him as a potential rival. The conflict has some merit in this story because you get the impression these two really don’t like each other. In the sequel Vader’s choking folks left and right like that’s his job, so this scene doesn’t have as much weight in that context. But in the context of the first Star Wars movie, it looked like Vader and Tagge had an almost personal enmity between them.

I mention this only because the House of Tagge later becomes a prominent early-EU villain in the Marvel comic. General Tagge’s brother, Baron Orman Tagge, hates Vader for blinding him with his lightsaber. Apparently in the EU Vader just made a hobby out of tormenting the Tagge family. But I’ll get to that.

The House of Tagge has a very influential corporation in the EU that is responsible for many of the weapons used by the Empire. Even in later works the Tagge company, TaggeCo, is mentioned from time to time.

I’m not sure how this factors in, but Tagge’s portrayal in the novel as being opposed to Vader may have mistakenly elevated the House of Tagge as Vader’s rivals in later works. In the finished film it isn’t even Tagge who mouths off at Vader and is choked for it, but Motti, so the reversal of the characters in the book may have inadvertently made the Tagges a lot more important to the Star Wars Universe than they deserved.

The turnaround in the novel didn’t just confuse me. In Starlog #120, a special tribute to the tenth anniversary of the first Star Wars film, there is a retrospective of the Marvel Comics series where the Tagge family are identified as the family of the general Vader choked. Whether this is the case in the comics or not is unclear; all the generals in that scene look basically the same. Baron Tagge’s animosity comes from being blinded by Vader, not from anything to do with his brother, so it ultimately doesn’t matter who Vader choked.

Here’s another thing that happens in the Star Wars novel that took me by surprise: Chewie talks! Sort of. In the movies human characters speak to non-humans in English and are understood, while they just as easily understand the non-human speech that is barked back at them. In the book these conversations are described as taking place entirely in the native tongue of the species in question. When Obi-Wan talks to Chewbacca he is doing so in the Wookiee language, and when that conversation is over Chewie tells them to come with him to meet Han in passably understandable human speech. This only happens in the Mos Eisley scene, but it’s still a little off-putting when you read it. Who knows? Maybe this helped to inspire Timothy Zahn, because years later he actually created a wookiee character for his novel Heir to the Empire, who was able to speak and be understood by humans due to a speech impediment.

Here’s one important difference between the novel and the film: At the end of the book, Chewie gets a freakin’ medal! All my life it seemed unfair that Luke and Han got a big ceremony and medals and all that business while Chewie just stood there like “okay, I was the one you talked Han into coming back, but whatever...”

Well, in the book, Chewie gets his own medal. Not sure why that ended up getting written out of the story by the time it was filmed, but in the novel and later on in the comics adaptation Chewbacca is duly recognized. This suggests that it happened in the early version of the script both adaptations were using as source material.

The snubbing of Chewbacca is explained away by an early example of revisionist history. In the Q&A section of the second issue of The Official Star Wars Fan Club Newsletter, the question is posed as to why Chewbacca does not receive a medal at the end of the first film. This is their answer:

The Rebel forces wanted to give Chewbacca a medal for his part in saving Princess Leia and in the destruction of the Death Star, but Wookiees don’t approve of medals. So, respecting Chewbacca’s wishes, they didn’t give him one. They didn’t want Chewie to go totally unrewarded, however. So, after the ceremony at the Rebel base, they flew to the Wookiee planet for a celebration.

One might argue that an imaginary ceremony off-screen isn’t much consolation. But when you consider the terrible consequences that occur when they actually do film a story about the rebels converging on the wookiee planet for a celebration, you can see why the wookiees disapprove of such things.

But we’ll get to that later.

None of these discrepancies make the novelization of the film any more an expanded part of canon than any novelization of any film would be. What makes this work interesting is that it was only the first part of a larger assignment Alan Dean Foster was contracted to complete. The author was given access not only to early drafts and notes, but also to the production sets of the first Star Wars movie. This was essential because Foster needed to understand how the Star Wars universe worked. Not simply so he could write a competent novelization of the first film, but also because he had been hired to write a sequel.

[1] Interesting side note: Windy’s last name in the EU is Starkiller. Windy and Deak’s names reference the main character of the first draft of the script, The Adventures of the Starkiller, which starred an early prototype of Luke Skywalker, then named Deak Starkiller.